Research into the Digital Divide in Canada

Rory O’Brien

Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto

July 23, 2001

In this paper an overview of the research done on the digital divide in Canada is presented. It provides an account of the latest statistics on access and usage, outlines the nature of the research efforts conducted over the last eight years in the area of public policy and advocacy, lists the strategy components of the Government of Canada, and discusses the upcoming issue of broadband access. Finally, it concludes with some brief mentions of areas worthy of future research.

Latest statistics on Internet access and use

Statistics Canada has been conducting surveys on Internet access and usage for many years [see http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/56F0003XIE/products.htm].

The following are some of the findings of a 2000 Statistics Canada survey of 25,090 respondents ("General Social Survey: Internet use 2000," 2001):

- 53% of Canadians over 15 years of age said they used the Internet sometime in the last 12 months [in 1994, there were 18%]

- 50% of women used the Internet, compared with 56% of men [in 1994, 14% women, 22% men]

- usage declined with age, with 90% of teens 15 to 19 online, compared with 13% of those 65 to 69

- while household connections increased 6% during 2000, there was no increase in the percentage of individuals saying they have used the Internet in the past 12 months

- 61% of people in Alberta and British Columbia used the net, while only 44% of those in Newfoundland and New Brunswick do

- 55% of urban dwellers used the Internet, compared with 45% in rural areas

- 79% of those with university education were online, but only 13% of people with less than a high school diploma

- 30% of individuals in households with income less than $20,000 had used the Internet, compared with 81% of individuals in households with an annual income of $80,000.

- age and income gaps were starkest in the 55 to 64 year olds, whose Internet use increased from 8% of those with less than $20,000 household income to 77% of those with more than $100,000 income

- 44% of francophones used the Internet in 2000, compared with 58% of anglophones

- Almost 40% of francophones felt there was not enough Internet content in French.

- Regarding online activities,

- 85% used the net to e-mail, with two-thirds of them using e-mail several times a week

- 75% searched for goods and services (though only 24% made online purchases)

- 65% surfed news sites

- 46% sought out health and medical information

- 41% accessed government programs and services

In summing up the digital divide as described by this survey, Dryburgh writes,

“Internet users differ from non-users in average age, education, and income. Non-users of the Internet are more likely to be older individuals, and are more likely to have less education and lower household income than Internet users. Non-users are more likely to be women than men at every age group. Francophones are less likely to use the Internet than anglophones, and those living in rural Canada are less likely to use the Internet than urban dwellers.” (Dryburgh, 2001)

The main reported barrier to accessing the Internet is cost, especially for younger people and those with incomes less than $30,000 a year. Among those earning over $50,000 a year, lack of time is an impediment to use. Lack of access to computers or access services also precluded Internet usage.

An intriguing finding was that only 27% of those not yet online expressed an interest in using the Internet, meaning that 73%, or almost three-quarters of the offline population, were not interested. While almost half of people aged 15 to 24 were interested in getting online, only 8% of those aged 65 to 74 were. This is an important item to note, and it has been extensively explored by Andrew Reddick in a research report called The Dual Digital Divide (Reddick, Boucher & Groseilliers, 2000). Reddick differentiates the first divide, between those connected and those not, from the second divide, between those who want to get connected and those that do not. He categorizes the latter into 3 types: 1. those ‘near-users’ who face cost and skill barriers but perceive value in getting online (women mostly), 2. those who face similar barriers but have only a limited sense of value, and 3. those who face barriers and have no value perception (mostly seniors). He recommends some ways to overcome the barriers and improve the perceived value of connection among the 3 types.

Public Policy Research

Aside from statistical surveys on Internet usage, much of the research on the digital divide has focused on public policy surrounding the implementation of the Internet in Canada. Several researchers in particular can be singled out including: Andrew Clement (Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto), Leslie Regan Shade (Department of Communication, University of Ottawa), Michael Gurstein (Associate Chair in the Management of Technological Change, University College of Cape Breton), Liss Jeffrey (McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology, University of Toronto), Vincent Mosco (School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University), Andrew Reddick and Phillippa Lawson (Public Interest Advocacy Centre), Garth Graham (Telecommunities Canada), and Marita Moll (Canadian Teachers Federation).

They are proponents of a vision of Internet implementation that is at odds with a perceived corporate view of the Internet as an online shopping mall. These individuals and organizations express a desire to see the evolution of the Internet driven by the local needs and decisions of people as citizens, rather than consumers. To these advocates, “cyberspace is public space” (Yerxa & Moll, 1995; Graham 1996; Menzies, 2000; Mosco, 2000; Moll & Shade, 2001).

The Universal Access Project

Andrew Clement at has been at the forefront of research into the policy implications of the Canadian digital divide. From 1995 through 1998, under the auspices of the university’s Information Policy Research Program, Clement worked with many of the aforementioned colleagues and his graduate students on the Universal Access project. The aim of the project was to produce a series of forums and discussion papers, emphasizing the role of local community involvement in Internet usage and the need to promote the new medium as a public forum.

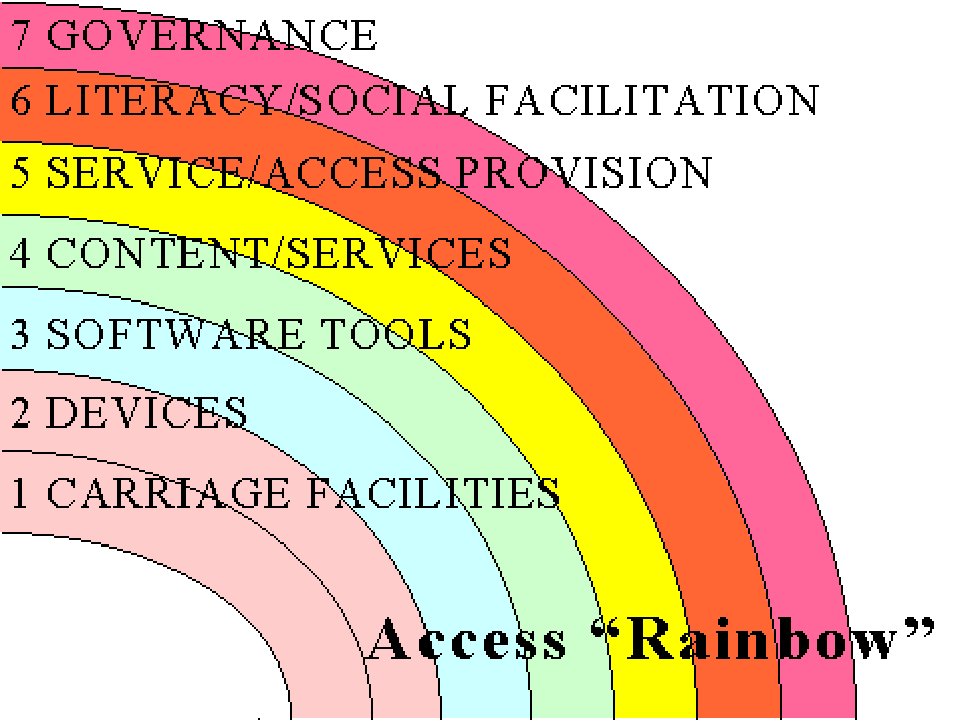

One of the more interesting conceptual models of Internet access that arose from the Universal Access project was devised by Clement and Shade (Clement & Shade, 2000). The Access Rainbow splits a number of elements related to access into a spectrum of seven items ranging from technical to social concerns (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Access Rainbow

Source: Clement, A. & Shade, L. R. (2000) The access rainbow: conceptualizing universal access to the information/communication infrastructure

- Carriage – the infrastructure for transporting the data

- Devices – the computers and other devices used by the individual

- Software Tools – the browser, emailer and other software software needed to use the Internet

- Content/Services – online databases and website repositories of information; email and e-commerce services

- Service/Access Provision – local ISPs and community access points

- Literacy/ Social Facilitation – text and computer literacy; training and support services

- Governance – public consultation on policy issues; social impact assessments

According to the authors,

“A key feature of this model is that it illustrates the multifaceted nature of the concept of access. Inspired by the layered models used for network protocols, the lower layers emphasize the conventional technical aspects. These have been complemented with additional upper layers emphasizing the more social dimensions. The main constitutive element is the service/content layer in the middle, since this is where the actual utility is most direct. However, all the other layers are necessary in order to accomplish proper content/service access.” (Clement & Shade, 2000)

It is a tool that has proved useful in separating carriage from content issues and has been effective in conceptualizing areas of needed facilitation in creating a working network of social service providers (Mielniczuk & Clement, 1996) as well as gaining a better understanding of gender issues in access projects (Balka, 1997).

The research synergies of participants resulted in several other papers and commentaries (see http://www.fis.utoronto.ca/research/iprp/publications/index.html), and culminated in a set of recommendations on a National Access Strategy (Information Policy Research Program, 1998). These recommendations included:

- establish a national task force on universal access

- identify an initial set of 'essential network services'

- establish a 'universal access fund'

- promote the development of a community technology sector as a sustainable solution to specific access issues

- create viable 'electronic public spaces'

- support on-going public interest research

- establish government information and communication procurement priorities to promote social objectives

- develop new legislation specifically addressing new electronic media

- establish

a "national access council for a connected canada"

("naccc")

Community networks in Canada had their beginnings with the FreeNet movement modeled after the Cleveland FreeNet in the U.S. In 1992, the Victoria and National Capital Freenets started providing free access to the Internet. By 1995 there were 24 cities with Freenets (Avis, 1995), and 60 by 1998 (Surak, 1998). Over the past few years, however, there has been a marked decline in the number of early-initiated freenets operating in larger urban centres, primarily due to fundraising difficulties. Telecommunities Canada was incorporated in 1994 as an community network umbrella organization for purposes of coordination and advocacy. It has managed to produce a number of papers and reports on community networking issues [see http://www.tc.ca/tcadvocacyandreports.html].

The Coalition for Public Information (CPI) is a non-profit organization created to ensure the Internet was deployed in manner that strengthened the public sphere. It was quite active in the years 1993 to 1999, but has since become somewhat inactive. One of their main contributions to the policy debate was establishing a number of discussion forums, both on- and off-line, to obtain public input into the proposed Information Highway. This effort resulted in a document called Future Knowledge: The Report - A Public Policy Framework for the Information Highway, in which a national vision was articulated, one that was based on citizen networking and equity of access (Skrzeszewski & Cubberley, 1995). Over the next several years, CPI worked closely with other advocacy groups to get its message out. Unfortunately, its message was not closely heeded by the decision-makers at the upper levels of government, according to Cheryl Buchwald, a PhD student who did her thesis on assessing CPI’s relevance to the policy-making process (Buchwald, 1999).

This paper is too short to go into detail on many of the issues raised and the stances taken, but it is generally felt among the advocacy community that regardless of the government rhetoric on listening to stakeholders and upholding the public interest, the corporate agenda has had ascendancy on Internet policy matters.

Government Strategy

Canada has been lauded as one of the most advanced Internet countries in the world. This has been attributed to the many government programs that have helped promote Internet access across the country. The Canadian government strategy is called ‘Connecting Canadians’, and according to Steinour

“The Connectedness Agenda is organized along six pillars:

1. Canada On‑line ‑ provide all Canadians with affordable access to Canada's world‑leading Information Highway infrastructure ;

2. Smart Communities ‑ partner with communities and local industry to support pilot projects that use information and communications technologies (ICTs) to link people and organizations together, stimulate productivity and innovation, foster demand for high technology goods and services and address local economic and social needs;

3. Canadian Content On‑line ‑ increase the availability of Canadian content on‑line ‑ content that reflects Canadian values, achievements and aspirations, and promote Canada as global supplier of digital content and advanced Internet applications;

4. Electronic Commerce ‑ implement a leading‑edge domestic policy and legislative framework (privacy, security, digital signatures, standards, public key infrastructure, tax neutrality, intellectual property and consumer protection), promote it internationally, and stimulate the development and use of electronic commerce by consumers and business to make Canada a global centre of excellence for electronic commerce;

5. Canadian Governments On‑line ‑ provide Canadians with on‑line access to government information and services; and

6. Connecting Canada to the World ‑ promote a brand image of Canada as global centre of excellence for connectedness by working with international bodies to harmonize regulatory and policy frameworks, by promoting Canadian best practices to other countries, and by promoting global interconnectivity and interoperability of broadband networks, applications and services.” (Steinour, 2001)

There are a number of government programs that have been successful in implementing the ‘Carriage’ and ‘Devices’ aspects of the Access Rainbow, and somewhat successful in the ‘Tools’ and ‘Content’ areas. But it is still a question as to whether the ‘Access Provision’, ‘Social Facilitation’ and ‘Governance’ parts of the Access Rainbow are being adequately covered [see Appendix A for a listing of government programs].

Project evaluations as research documents

The literally thousands of implementation projects, funded 50% by these government programs have amassed a great number of research documents in the form of project reports. Much of the research on how the information and communications technologies are being used by some ‘have-nots’ segments of the population has been associated with the Office of Learning Technologies (OLT) program of Human Resources and Development Canada (HRDC) [see http://olt-bta.hrdc-drhc.gc.ca/]. In several instances the research projects were carried out by researchers associated with particular university programs. The following are but two examples contained in the set of reports.

For users in rural and remote areas

The Centre for Learning Technologies (CLT) and the Rural and Small Town Programme (RSTP) teams at Mount Allison University engaged in a study of the academic upgrading needs of adult learners and economic development volunteer learning needs. Working with participants at nine CAP sites in New Brunswick, they concluded that while more research was needed, there should be more emphasis placed on adequate recruitment and screening for ensuring commitment, more support materials, facilitation and monitoring are needed (Mount Alison University, 1999).

For seniors

Researchers at the Seniors’ Education Centre, University of Regina worked with 300 senior citizens age 55+ over a period of two years in forming a computer club. The methods devised for encouraging interactive use, as well as for implementing a train-the-trainer program were deemed to be successful (Seniors' Education Centre, 1999).

Broadband - the next big policy issue

As the number and range of applications and services that require multi-media increases, so does the demand for high-speed Internet access. To advise the federal government on how best to facilitate the roll-out of such high-speed connectivity, the National Broadband Task Force was established in 2000. The multi-stakeholder Task Force included 36 members, the majority of whom were CEOs of large media corporations. Working in conjunction with inter-governmental bodies, it solicited research on the current state of affairs of broadband service availability. The following are some statistics on the current state of broadband in Canada.

Municipal access

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities, in a survey of just over half of the 4,070 municipalities across Canada done in late 2000 as an input to the task force (Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 2001), found that:

· 72% had Internet access via a local or toll-free number

· 7% report that the only means to access the Internet is though satellite technologies.

· 36% had high-speed Internet services available through the phone [81% in cities over 100,000]]

· 29% had high-speed Internet service available through a cable company [85% in cities over 100,000]

· 19% have implemented a community fibre network approach [39% in cities over 100,000]

· 75% have wireless telephone service [86% in cities over 100,000]

As can be seen, the larger the municipality, the greater the availability of high-speed Internet access.

Rural access

In the last quarter of 2000, the Rural Secretariat of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada commissioned a survey of 5,000 rural and urban residents and found that:

· 32% of rural respondents indicated they had no access to the Internet compared with 24% in urban Canada

· 34% of rural Internet users experienced high comfort levels with using computers, compared to 46% of urbanites

· 86% of rural users used dial-up modems from home, compared to 66% of urban dwellers, while 12% used cable modems, compared to 26% respectively.

In its report on these findings to the Task Force, it emphasized that the digital divide between urban and rural residents is increasing – “whereas the percentage of urban households connected to the Internet increased from 30% to 47% from 1997-1999, rural connectivity increased from 20% to 35% in the same period”. (The Rural Secretariat, 2001).

Major findings and recommendations of the National Broadband Task Force include:

· All Canadians should have equitable and affordable access to broadband services;

· Focus should be on communities where the private sector is unlikely to deliver services;

· First Nation, Inuit, rural and remote communities should be a priority along with public institutions (learning institutions, libraries, health care centres and public access points);

· Investment estimates for deployment of broadband infrastructure vary widely depending on whether they include support for transport to communities or access within communities, as well as depending on the combination of technology solutions;

· Accessibility means more than infrastructure - it also means content, services and building community and individual capacity;

In response to the Task Force report, there were a number of critical suggestions made. A key one was a warning to consider the need for the technology, i.e., the ‘first mile’ rather than the ‘last mile’. Providing technical access capabilities alone is insufficient; “useful access”, a mixture of both locally meaningful content and supportive promotion of emergent services is something that should be planned and cultivated prior to technical provisioning (Civille, Gurstein & Pigg, 2001).

Conclusion

This paper has examined the various research sources and findings regarding the digital divide in Canada. Future research must look at such things as the effect of the Internet on public discourse, the degree to which the corporate agenda may be at odds with a vision of civil society and how that plays out in the evolution of the online environment, how the unconnected may be affected by an eventual replacement of government offline services with online services, and finally, how broadband and media convergence will exacerbate access issues.

Appendix A:

Canadian Government Programs to Reduce the Digital

Divide

As of July 18, 2000, http://www.connect.gc.ca/en/130-e.htm