The Information Revolution and Human Learning

Bob Thomson bthomson@web.ca

With all the hype in the press these days about the information superhighway, artificial intelligence, chat bots and the use of computers to provide us with information, knowledge, wisdom, and false news, it is important that we understand a few basic concepts about human knowledge and learning, in order to avoid unrealistic expectations and to put the information revolution into a context that we can deal with in our daily lives.

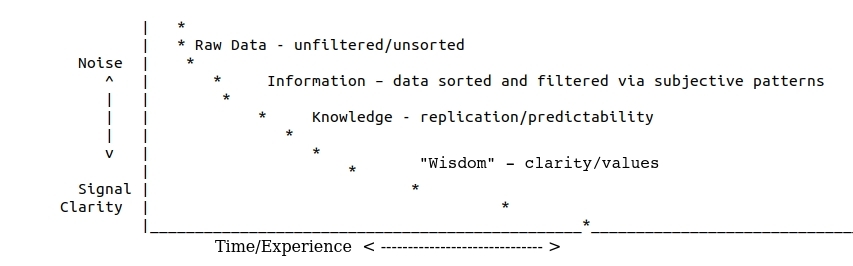

In 1980 Irish engineer Mike Cooley outlined the process whereby we sort the raw data which comes into our lives through our eyes, ears and other senses, over time or with experience, and how each of us progressively turns this data into information, then knowledge and eventually wisdom. This is the learning process, and we all use it every day. The vertical axis of his graph below shows "noise" or a measure of unintelligibility at the high end and "signal" or clarity of understandable patterns at the low end. The greater the signal, the more synthetic or “useful” the information.

At the core of this learning process are the highly subjective filters that we all use to identify patterns in that raw data: language, race, gender, religion, political beliefs, scientific “facts”, etc., to turn it into information. These filters are key, as information and disinformation increasingly dominate the press, media, academia and education systems based on the subjective filters of those who have the resources to access, sort, synthesize and present it to us as information out of the mountains of “data” now electronically available more or less freely via the internet. The Guardian recently noted that artificial intelligence and some recently developed chat bots are fallible, and not immune to these “selective” subjective filters!

The time/experience axis above is deliberately shown as bi-directional. At any point in the process of learning, we might, and often will, or should, discover a flaw or necessary refinement in the filters and patterns we used to move from one step to another, at which point we need to, and should, go back and, using our new filters, re-sort the original "data", along with any new "data", to arrive at new "information" and eventually new "knowledge" and "wisdom".

On my own learning curve(s), I married a feminist and changed my gender filters to arrive at new information. My first job after graduation was in Peru, learning Spanish and Quechua and helping build community projects in the Andes. I was once told by an Algonquin colleague that I didn’t understand something because my first language was English. She noted that the majority of words in English are nouns, while verbs dominate Anishinaabe languages, with the result that they have a view of the world based on action and process, while we see it as things. My filters changed and new patterns emerged!

One aspect of the information revolution is that there is so much data available now that we give up trying to sort it ourselves. In doing so, we can succumb to chaos and powerlessness, giving up personal empowerment and knowledge to "gurus" who claim to have it sorted already and to serve it up to us in intelligible packages, with no effort required on our part to do any of the sorting ourselves with our own (subjective) filters. With global access to information through television and the press, the incredible complexity of the world and humanity becomes very evident, while at the same time, giving power to anyone with control of television, media, the press and Internet content to spoon feed us with pre-sorted, simplistic "information" based on their own religious, political or economic patterns and interests, i.e. their cultural narratives, not ours.

Scott Staring recently noted that the basis of knowledge now vastly exceeds individual human memory. He notes that “The idea of knowledge as something that someone builds and holds within their mind, as it were (metaphors are inescapable when speaking about the mind), is rapidly being eclipsed by a view of the Internet as a prosthetic brain that more or less obviates the need for memorization.”

Yet, while potentially frightening, the information revolution is also promising. Our growing democratic capacity to analyze old and new economic and political models can bring despair, but also hope. Computers can now help us access, analyse and synthesize huge data sets and identify new patterns and new alternative information, knowledge and wisdom, for example to develop new low carbon models of cooperation and solidarity. Examples are Piketty's 1% vs 99% and Vettese’s analysis of the economy of half earth, which show how "popular" access to and analysis of historical economic, energy, climate and other data can be used to develop alternative models and behaviours for a transition.

In a recent piece I briefly reviewed some of these alternatives: The Peer to Peer Transition to the Commons, Green New Deal(s), Degrowth and the indigenous concept of "buen vivir" - and the promise and difficulties of implementing them. Thousands of individual and confederated local, community and regional examples already exist as lived examples of alternatives and progressive social media and cooperative networks which challenge the capitalist mainstream. As pluralistic cultural, political and lived alternatives and systems, they show that people can live well together and with nature.

934 words to here